POPLITEAL SCIATIC

I consider this block to be one of the basic blocks that should be learned early in the course of converting to ultrasound and continuous nerve blocks. Of the sciatic nerve blocks, it is the easiest to incorporate ultrasound (no matter your original approach or patient positioning), it is a superficial block which allows for a perpendicular needle approach and there are several ‘guideposts’ to clearly identify the nerve.

Some of the points I make here will likely be repeated on the YouTube links below, but hopefully it will be a case where the repetition is a positive thing and not a bore. This block can be performed in the supine (with the calf elevated), prone and lateral position successfully with ultrasound, and I know people who use each. I think it is easiest to learn in the prone position for several reasons. One is fatigue. It is necessary often to press hard to visualize the structures for this block, and hand fatigue is a real factor. It is easier to press down than up (using your weight or triceps rather than your anterior deltoids) especially for extended periods of time. I find it easier to press the leg into the bed (or into my thigh in the case of a more lateral position which I use) instead of into the air (when supine and calf elevated) to get the compression necessary for good visualization. Also, with the prone position, the probe is oriented the same as the ultrasound screen (though some screens allow for rotating the screen 90 or 180 degrees to match your orientation) with the probe on the top of the patient. Lastly, it helps to look down at the back of the thigh as you visualize the structures that are beneath the skin and their orientation to one another. It allows as well the ability to recognize landmarks when asking the patient to flex at the knee to help you orient (or reorient) yourself properly. Building these 3-D visualizations in your mind is a key tool to adapting to ultrasound (and it is also very helpful with nerve stimulation as well).

The downside of the prone position is the extra time and trouble it takes to flip over especially when a saphenoous block is planned as well because you will need to flip back again. It knocks EKG leads off and takes forever with a hurting or sedated patient. If it helps you to do the block effectively, then do it this way until you don’t need all of these aids.

The easiest position is to just elevate the calf of a supine patient. You need a reliable and always available system for this. I have used an expensive leg holder that our Podiatrist uses in the O.R., and I have seen variations with the use of a Mayo stand and pillows or wads of those blue or green O.R. towels taped together. This is usually a more gentle approach for the patient who is already in pain. With a supine position, it allows some to use a ‘one hand sterile’ appraoach where the probe hand is under the leg and away from the sterile block site. It used to take the ‘up is down’ switch in your brain to perform this block, but that is not a challenge if you have the right ultrasound machine. Once the leg is lowered, you are already in the correct position to do the saphenous block.

I have become accustomed to using a lateral positioning of the patient. I have them turn (carefully if they are in pain, of course) with the surgical side up, then allow the knee of the upper leg to fall forward onto the bed. I stand on the side that the patient is facing. With the bed high enough and the ultrasound machine directly across from me, this is ergonomically a very comfortable position for me to do the nerve block.

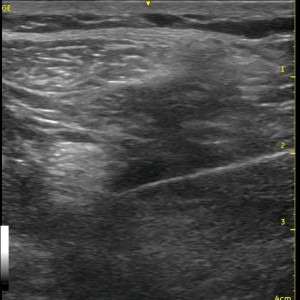

The biggest advantage to ultrasound is seeing the needle path and the surrounding structures, therefore I use an in-plane view of my needle and a short axis view of the nerve whenever possible. For the poplitel block, that means a lateral approach. One of the YouTube videos desribes this approach in detail. I use an 18 gauge needle (see Tip of the Week section for more details), and ultimately leave the catheter on the medial side of the anterior surface of the nerve to have ‘track back’ work for me. This also orients the catheter with multiple orifices against the nerve. With very muscular people, however, I have found it easier to get to the nerve from the posterior approach with an out of plane needle and short axis view of the nerve or even an in-plane needle approach and long-axis view of the nerve. The other option is to move distally where the musculature falls away to the sides unless the nerve splits apart too far for one catheter to cover them. See the cadaver pictures below. Many people begin scanning at the popliteal crease where the vessels are apparent as markers for the nerve, then they scan proximally. My approach is just the opposite as discussed on the YouTube links below.

I would now like to focus on some anatomical points with this nerve block. I think of the Biceps Femoris and the Semimembranous/Semitendinous muscle as each of two sides of the roof of a house covering the sciatic nerve which sits just below. See the cadaver pictures below for an illustration of this concept.

Notice below the orientation of the Common Peroneal and Tibial Nerves below. The Tibial Nerve continues in a relatively straight path just superficial to the Popliteal vessels while the Common Peroneal Nerve takes a lateral (downward in the picture below) course. What that means is that it makes sense that when using nerve stimulation, we often first encounter dorsiflexion and eversion (Common Peroneal response) then if we keep advancing, we switch to plantar flexion (Tibial response). If these responses change with millimeters of needle adjustment, then the individual nerves are still one unit or very closely approximated. If there is some distance between responses with no response inbetween, then the nerves have separated at this point. Without ultrasound, we would have to guess whether or not we are ‘close enough’ to inject our local. It also will tend to lead to the use of greater volumes ‘just in case’ we don’t get the desired path of spread.

Utilizing ultrasound, we select the point at which the nerves are as separated as we want them to be. Some choose to inject at a point just where the two nerves are moving apart because there is more surface area (leading to a quicker block set up) and to make it easier to ‘pop’ into the outer connective tissue/perineurium without impaling the nerve. All reasonable goals and reasoning. There are some technical skills to learn with needle dexterity and control of the probe before one starts to manipulate the nerve to this degree. Sometimes the anatomy works out perfectly, but given an ‘either or’ scenario, I select a position a little more proximal where the nerve is essentially one unit, I stay away from the vessels (and that is what I would tell you to do if you are a realtive novice) and just confirm a circumferential spread of local. With this approach, I do not have trouble with a ‘patchy’ or shorter than expected block. I do not always take time to penetrate the perineurium to get these results either.

I look at it with a catheter technique like watering flowers. I only have one water hose, so I leave it where the flowers are close together so they all get water. Unless you confirm that you are within the perineurium, when the nerves are separated, the slow trickle flow may not reach all of the flowers. Consider the above picture with the catheter at the level of the white marker versus several centimeters distally where the nerve has split and has moved apart some distance.

Follow the links below to see an ultrasound video of the sciatic nerve at the popliteal fossa which scans from high to low and repeats as well as a short video from some of my Powerpoint lectures describing helpful points for identifying the nerve in this region.

See Also: The ‘Right’ Way