SUPRACLAVICULAR

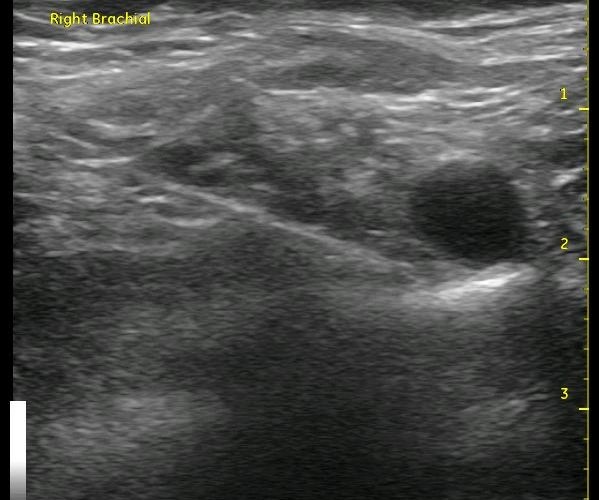

Above, you can see a needle advancing from the left of the image and piercing the middle scalene muscle to approach the ‘corner pocket’ at 2 cm depth. The muscle is indistinct due to the very steep angle at which it is being viewed. The ‘corner pocket’ is at the intersection of the rib, artery and the plexus. A single bolus here is almost always sufficient, however, if the neural elements are seen past the 2 o’ clock position or you need a really quick set-up for the radial aspect of the hand, it is best to inject more in the center of the plexus. Either way, stay away from multiple passes as small vessels can be all around, and it is just not necessary. More on this later…

‘Block People’ tend to be infraclavicular or supraclavicular proponents, and they tend to stick to their guns about why their approach is superior. Although I would recommend learning one well but then moving on to learn the other (for a variety of reasons), I must say that I am no different. I am an ardent fan of the supraclavicular block for single and continuous blocks of the humerus to anything in the hand, and I have what I think are very good reasons to stick to MY guns. When I learned how to do this block with ultrasound, I don’t think any other filled me with as much excitement because it was so simple, and it allowed me to take care of so many new populations of patients. Granted, if I had started with an infraclavicular approach, I may not have worked on my technique so mu ch and found ways around many of the complaints by some about this approach.

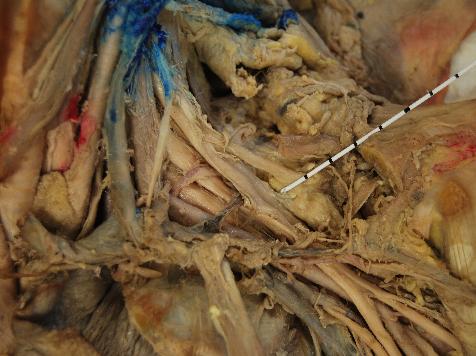

First of all, this block is very superficial which makes the surrounding structures easier to see on ultrasound because the sound waves have not degraded in various ways. This also allows for a ‘flat’ needle path to the intended target, so the needle is easy to see. Because of this, it usually takes one to three minutes to complete the block. Second, there is no ‘jockeying for position’ with the coracoid process. (I know that Stuart Grant at Duke commonly uses a supraclavicular approach to the infraclavicular block which obviates this fight, but it is still a deeper plane to maneuver. I intend to start this approach myself soon for the sake of experience…when I find a good reason to switch. Ha!) Lastly, though going through a lot of muscle tissue holds an infraclavicular catheter well, you have to go through a lot of muscle tissue. I the image below, an approximate needle course is demonstrated for the supraclavicular block.

The common criticisms of the supraclavicular approach include some degree of phrenic nerve palsy, ulnar sparing, poor catheter securement and various blood vessels which can get in the way of the target. I would consider doing an infraclavicular block over a supraclavicular block for a pulmonary cripple in order to avoid the possible respiratory embarrassment if I felt like I needed large volumes for the block. I have been able to get around the leaking catheter problem by extending the distance between the target and the skin entry site at least 6cm or so (This might correspond to an area at the skin near the wide 5cm mark on the above needle). Further, I recognize that there are several blood vessels (sometimes the vessel is actually the omohyoid muscle) that can get in the way of my intended needle path, and that is a valid concern. I have almost always been able to redirect the ultrasound beam slightly to find an unencumbered path to my target. I understand that ulnar sparing can happen with an interscalene block, but I just haven’t run into that problem myself with supraclavicular blocks. I’ll just have to watch someone who on occasion runs into that problem and see what we are doing differently.

My basic technique is to place the linear probe above the medial aspect of the clavicle, leaning from a coronal toward a transverse plane (somewhere between these two planes) looking for the pulsating subclavian artery. I then rotate the …

REGISTER for FREE to become a SUBSCRIBER or LOGIN HERE to see the full article!